Why does an intervention work in one neighbourhood and not in another? And why do local actions quickly arise in one district to deal with changes and why does this process barely get going in another district? There is a good chance that the social structures of the neighbourhoods are different. One neighbourhood may have residents interconnected within local networks, while another neighbourhood may operate as separate islands. This affects the way information spreads. In one neighbourhood, sharing messages in WhatsApp groups can be the determining factor, while in another place it is about the meetings in the community center and the local library.

Networks as a starting point for the practice of neighbourhood development

Networks in neighbourhoods are important to be able to deal with changes locally. The future is uncertain, but the importance of a strong local network to adapt to a changing context is a constant. A strong local network cuts both ways, it gives residents the opportunity to help each other, take collective action and influence local developments, and when institutions have a better understanding of the structure of local networks, participation and cooperation processes can improve by providing tailor-made implementation and communication. In this way, resources can be used purposefully and effectively, while the well-being of residents takes priority.

Strong social networks in neighbourhoods are often invisible to outsiders. That is why this online neighbourhood network instrument aims to provide insight into active networks in neighbourhoods for a broad group of professionals and interested neighbourhood developers. The instrument can be used by anyone via a web page, but the tool is targeted at people who want to work in a neighbourhood-oriented manner, such as researchers, social entrepreneurs, policymakers and area workers. In previous research projects, we identified that this group often want to cooperate with the neighbourhood, but do not always know how and where to start. For them, this instrument is a starting point to better cooperate with the neighbourhood. For example, formal developments can better build on what is used and valued locally.

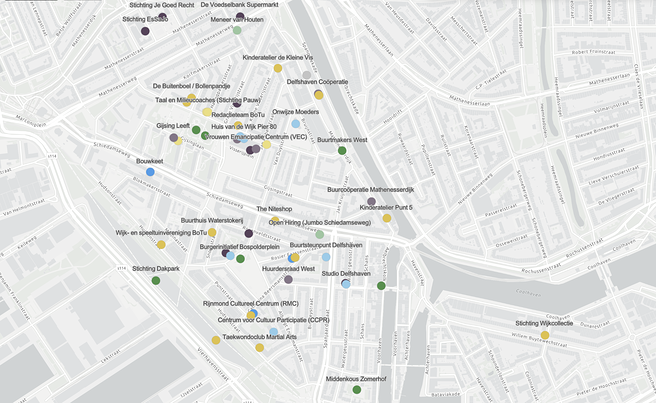

The instrument provides insight into the dynamics and degree of organization of Rotterdam neighbourhoods. It thus increases the chance of collaborations between existing initiatives, key figures and formal actors. The starting point is that it is easier to find an entrance to the local network. Even in situations where cooperation is not desirable, it is still good to know what else is happening in a neighbourhood. The instrument provides insight into the characteristics and the concentration of current developments. It also shows where the gaps are. This helps prevent duplication of work or getting in each other's way. The instrument offers the possibility of juxtaposing networks of several districts. It shows how the city functions as a network and what the differences and similarities are between neighbourhoods.

A new measuring instrument within the framework of current policy developments

Revealing how a neighbourhood manages to organize itself collectively is not yet common practice. Mapping out neighbourhood development in Rotterdam is done through other measuring instruments, such as the Rotterdam Neighbourhood Profile (‘Wijkprofiel’ in Dutch, a biennial residents survey that compares development in neighbourhoods). In addition to objective data, the Neighbourhood Profile also includes room for the subjective experience of residents. It can compare neighbourhoods well, but to understand a neighbourhood better, it lacks stories and faces to interpret average figures about a neighbourhood. The instrument makes the living environment of residents visible by giving the figures a face. It shows the contrasts and dynamics. In addition, it does not show a neighbourhood as a sum of residents, but provides insight into the local, collective strength and degree of (self) organization of a neighbourhood. For example, other neighbourhood users, such as entrepreneurs, also play a role in the instrument, people are given a place and a face and mutual relationships are central. The tool also differs from existing data maps such as the Data Plan (Dataplattegrond in Dutch) and the Social Facilities Map, which focus on formal data sources and facilities. In this instrument the emphasis is on the informal side of networks and facilities.

The development process of the instrument builds on insights and developments from previous projects, such as the Resilience Monitor in Bospolder-Tussendijken, supporting the Resilient BoTu 2028 neighborhood development program, and the Neighbourhood Identity(s) project. This provided, among other things, knowledge about community building and concrete products that we integrated into the instrument, such as the network map and initiative map. Although the instrument offers tools for a more targeted interpretation of figures and possibly for adjusting policy or implementation programmes, it is not intended to measure their effectiveness. However, it may contribute to informed policies in the future.

The neighbourhood network instrument is in line with current Rotterdam policy developments such as Wijk aan Zet and Resilient Neighbourhood Programmes. The expectation is that Rotterdam neighbourhoods will increasingly pursue specific local goals. Governments sometimes see initiatives and active residents as merely an instrument to make an intervention successful. In contrast, Wijk aan Zet requires a different form of governance and investment, in which residents direct neighbourhood development and the government assumes a responsive role. The instrument provides tools for responsive neighbourhood development by providing insight into where, how and why residents are already collectively organizing themselves.

Data sources

The social fabric of a neighbourhood consists of diverse networks of active people, leading initiatives and important meeting places. Together they provide a picture of how a neighbourhood functions as a collective. This information is not available in existing statistics and maps, but obtained by Veldacademie and its partners by conducting (street) interviews.

The qualitative data was collected in conversations with neighbourhood users and the initiators who improve the living conditions (social and spatial) for residents. These stories about initiatives and networks, together paint a picture of the neighbourhood identity(s). Because the neighbourhood network is constantly changing, the picture will never be complete or complete, but this is not a condition to be of added value.

An important starting point of the instrument is to relate these stories of neighbourhood users to quantitative data about the neighborhood and its residents. The data sources that we combine come from, among others, Veldacademie, CBS, OBI and fact maps from the Municipality of Rotterdam.

The development process: workshop series with various stakeholders

To develop the instrument, we set up a development process consisting of two parts. The first part aims to outline a common framework. This resulted in a 'Proof of Concept'. In this section we involve stakeholders in defining the building blocks and conditions for using the tool. In the second part of the development process, three sessions took place to test and improve the prototype with participants. The workshops and test sessions were aimed at the active participation of various stakeholders, such as policy makers, researchers and GIS experts, etc.

Credits

In this project we are working together with TU Delft's Citizen's Voice project team, consisting of a group of researchers from various disciplines, including urban planning, participation processes and digital tools. This collaboration came about under the umbrella of Resilient Delta, of which Citizen's Voice is a pilot. Both projects complement each other and can possibly reinforce each other.